Open Cybersecurity Alliance Adds Indicators of Behavior (IoB) Sub-Project

January 18, 2023

A Kestrel Analytics to Detect Lateral Movement

February 27, 2023Recently, the Open Cybersecurity Alliance announced that our Indicator of Behavior (IOB) Working Group has transitioned to an official sub-project within the Alliance. I wanted to share a little bit about this effort and explain why we want you to join us.

The main goal of the IOB effort is to create a standard way to represent cyber adversary behaviors to make it easier to:

- share repeatable sets of observed adversary behaviors spanning multiple campaigns,

- share the analytics to detect those behaviors, and

- create and share playbooks/workflows to correlate those detections.

To help explain why we feel this effort is needed, I’d like to take a moment to discuss how I came to join this effort.

Past experiences with Cyber Threat Intelligence

I’ve been a cybersecurity researcher for the last 14 years. Over that time, I’ve been fortunate to work on a large set of challenging research problems to create prototypes and pilots of new approaches to secure the networks that drive governments, enterprises, and critical infrastructure. I consistently see a common aspect across all cybersecurity: Cyberattacks occur at a speed and scale that makes it nearly impossible for any single organization to mitigate the threat alone. If we want to address attacks of this speed and scale proactively, our defensive communities have to work together.

I saw again and again that organizations needed to leverage automation and orchestration of their cyber defensive response to attackers who used their own automation to compromise our systems. However, the only way we could gain enough situational awareness to take action fast enough was to engage our communities in sharing information about the threat so we could know what attacks were targeting us.

We’ve seen that an effective defense couldn’t happen without leveraging the power of community, but it also couldn’t happen without a common language to share information, such as IOCs and CVEs. A common way to format and share these data was crucial for us to succeed in automating and orchestrating the sharing and response process. The STIX and TAXII standards managed by the OASIS standards body provided the key to achieving our results. We were ecstatic to pilot these capabilities that made it possible for one member of a community to respond to incoming threat information within minutes of another member observing that threat intelligence in the wild for the first time.

But it isn’t enough.

Motivation to represent adversary behavior

It’s critical that we block IOCs rapidly to prevent attackers from accessing our networks, just as it’s critical for us to address relevant CVE data to patch our systems against remote exploitation. However, we can’t limit our defense to those categories. By their very nature, efforts addressing IOCs and CVEs are reactive defense measures. Our attackers aren’t stupid. They know we share IOCs, and attackers constantly modify their infrastructure to rapidly discard known IOCs and move on to new ones. Organizations that only hunt for IOCs they find in threat reports are fighting against a drastically short timeline if they want to prevent an attack rather than discover that part of their network has been compromised. We need to begin a response within minutes, and that just can’t happen effectively when we respond to threat intel that is days, weeks, or sometimes months old.

That isn’t to say IOCs are worthless. But evaluating and blocking IOCs is a job for people leveraging automation, either through a SOAR platform or within their vendor-provided solutions. Manually evaluating thousands of IOCs daily is a loser’s game.

We need something proactive, and we need to make it accessible across our communities.

This has led us, and many other organizations across the world, to leverage sharing detection analytics and attack patterns, such as those found within the MITRE ATT&CK® framework. But we still see the barrier to entry as being too high for most of the world to take advantage of this information, meaning many networks will continue to be vulnerable to the countless successful cyberattacks we read about in the news on an almost daily basis.

MITRE ATT&CK® has made a tremendous impact in giving our global defensive community a common language to describe adversary tactics and techniques. This has helped all of us better understand what attackers are doing. However, successful detections aren’t written at the tactic and technique level. SOCs and hunt teams search for sequences of attacker procedures, hence why the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) together are so critically important. Frankly, it’s often not often even possible to write good detections at the “TT” level because that level is too broad. We share good, sound recommendations of what someone should do, but unless an organization has extremely skilled support (either within their team or via an external source), they can’t write those detections themselves.

This has led to fantastic efforts across our community to share analytics and hunt guidance. However, we share detections for one piece of the attacker’s actions. We do this because we envision each detection being its own alert monitored by a SIEM or an analyst. With that mindset, reducing false positives becomes paramount. We can’t expect someone to filter out hundreds or thousands of false positives daily, just as we can’t sanely expect analysts to manually enrich and hunt for thousands of IOCs daily.

In the effort to keep the false-positive rate low, phenomenally talented detection engineers create and share great detection analytics, but the detections are highly specific and rarely work beyond a specific adversary and specific threat campaign. Again, the speed and scale at which cyberattackers modify their attacks is a massive problem. Even organizations with extremely talented defensive support can’t tailor and update these detections fast enough to keep pace with the onslaught of attacks.

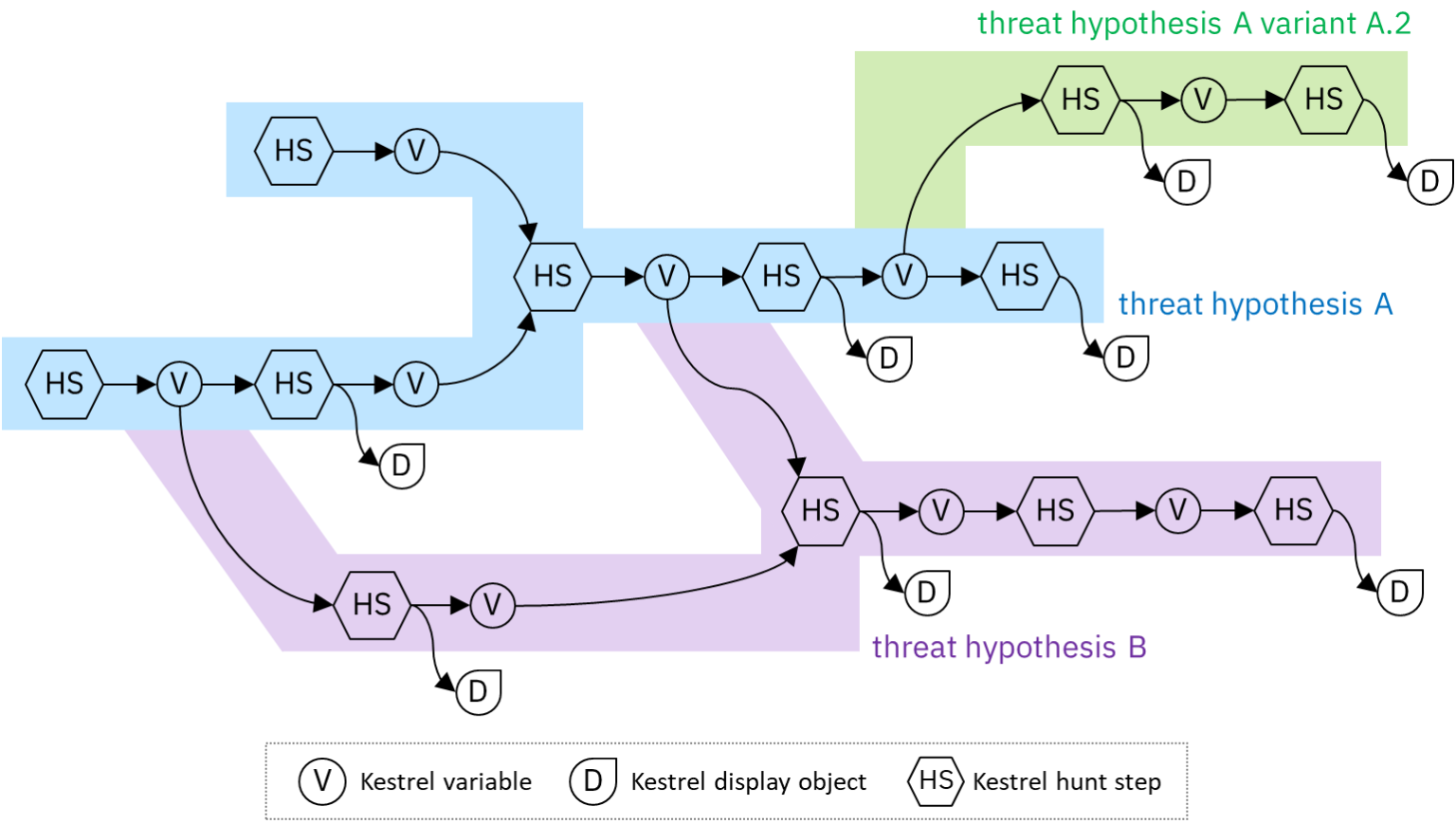

This is why we feel we need a different set of analytics to share—analytics that aren’t meant to be monitored by a human but rather tied to a set of correlations among alerts that are monitored by our security teams. By sharing sets of detection analytics where a single analytic may have a very high rate of false positives but certain correlated fields among those alerts have a very low rate of false positives, we can shift our thinking on how we write and share this information. We can now focus on the behavior of the adversary, which frankly doesn’t change nearly as often as they may change an IOC or a single procedure within their kill chains. As a simple example, consider this sequence of events:

- A user machine opens an email containing a link.

- That same machine runs PowerShell for the first time ever.

- The process spawned by PowerShell on that machine makes a Registry edit.

- A system-level process appears on that machine that was created by a user-level process.

A detection analytic for any single step in that sequence will likely have a false-alert rate that makes the analytic by itself not terribly useful. However, the ability to correlate common fields among those alerts could easily highlight suspicious adversary behavior on the network, namely someone attempting to spearphish a user, establish persistence, and escalate their privileges.

Rather than write detections for how the attacker accomplished these steps, we should write detections for what the attacker is attempting to do, hence detecting their behavior.

The challenge is that each correlation requires different fields to detect and different time windows for the correlation. This is why sharing a standardized set of analytics and a correlation workflow is needed. It’s unrealistic to believe that every organization will have the ability to run these correlations by themselves (many will be able to, but many more will not, especially the small- and medium-sized businesses that play key support roles to larger organizations). However, by making standardized sharing of this information possible, we enable key force multipliers in our collective defense through our managed security service providers, security vendors, and infrastructure vendors.

Join our effort

For that to work, we need to agree on what the information should look like and how to use it.

That’s why we made this sub-project within the Open Cybersecurity Alliance.

And that’s why we want you to help us take these steps. Membership is free and open to the public. Additional information about the IOB sub-project, including ways to participate, is provided in our overview presentation.

We have to work together, and I hope you’ll join us.

Learn more about IoB

If you want to learn even more about IoB and the OCA sub-project, there are two free events coming up:

- Q&A with the project leadership during next OCA Office Hours on 21 Feb at 04:00 PM EST

- Attend the IOB Webinar on 1 Mar at 11:00 AM EST

Charles Frick

Principal Staff, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) and Chair, Open Cybersecurity Alliance Indicators of Behavior Sub-Project